Feature F1 Unlocked

LIGHTS TO FLAG: How 1979 F1 champion Jody Scheckter 'hustled' his way to F1 and ended up farming

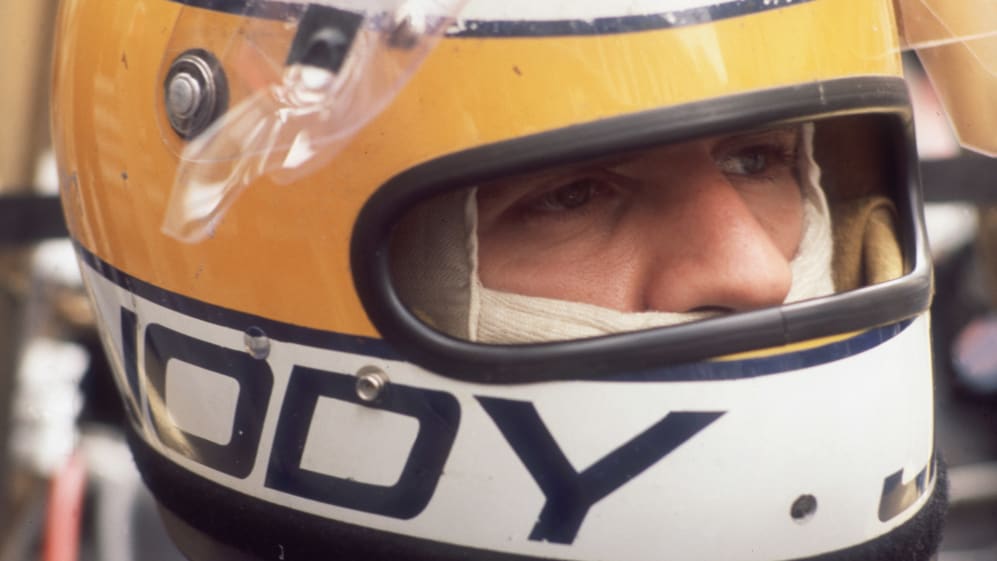

Lights To Flag is a new series that explores the challenges that drivers overcame to reach Formula 1, how their careers unfolded and ended, and – crucially – what retirement from F1 held in store for them. Jody Scheckter, 1979 world champion, tells us how he went from racing Renault saloons to taking on the likes of Gilles Villeneuve, before finding his feet in the world of firearms and farming.

Beating the works Renaults

Scheckter comes from a racing family, his uncle, Tom, having entered the pre-war 1937 South African Grand Prix and his father having owned garages in his home town of East London. Scheckter got his start in karts around the age of eight after his parents challenged him to better his failing grades.

“I was terrible at school, and my parents said, ‘If you come in the top four, we’ll get you a go-kart’, and they thought they had a safe bet on it. And I came fourth or something,” he says, leaning back and cracking a wry smile.

The racing bug was there, Scheckter's dyslexia doing little to sway him towards schoolwork as he says guides to modifying two-stroke engines fit perfectly inside his textbooks. With that, it's little surprise that an apprenticeship at his father’s Renault garage followed.

“My dad gives me an old Renault to go to work – I was a mechanic. So, I went to work once in it and then I started modifying it to race,” says Scheckter.

“There’s one guy that ran the works Renaults, a guy called Scamp Porter. And I raced against him and beat him, and I copied his car. In the races I used to go underneath his car and take everything, exactly where his distributors, coils were… mine were in the same place. I copied his car completely – and then started to beat him. I always remember, they modified their car for the next year, and Scamp came past my car and said: ‘That’s exactly the same as my last car!’ And that's racing…”

He adds, almost foretelling the story of his post-F1 journey: “That’s how you hustle.”

Scheckter would soon chalk up regular wins in the national saloon car series – shrugging off black flags for his sideways driving and mandatory National Service. Formula Ford, then McLaren, came calling.

From East London to North London

As a saloon car stalwart, Scheckter was offered a drive in Formula Ford and in 1970 he won the South African series to secure a place in the ‘Driver To Europe’ scholarship. He travelled to the UK with the cash prize, a hunger to race anything, and a looming culture shock.

“Well, I came from the airport, I’m now in Baker Street, and I’m thinking: ‘It’s still slums!’ It’s old buildings and lots of these little semi-detached [houses] and everything. I lived in a house with, I think, six other journalists, and they wouldn’t let me have a bath every night because I used too much hot water – Andrew Marriott [journalist and author], he was one of them!

“I went and stayed with them because I had no money, and I’d have to go and eat cheap meals. What was cheap? Indian food cost 20p if I remember. So, I’d eat that – I’d try and survive.”

PODCAST: Jody Scheckter on his 1970s rivals, Enzo Ferrari and life after F1

With some help from his new flat mates, Scheckter would manage to wrangle a Merlyn Formula Three chassis, chalk up some wins in that – though he makes sure to interject “I crashed a lot as well” – before McLaren offered him a Formula 2 drive.

“And I won a race at Crystal Palace in Formula 2 – there were Formula 1 drivers in that field – and that’s the first time I thought I was good enough to make the next step. But I don’t remember ever thinking ‘I want to be a Formula 1 driver’.”

As for the flat in Baker Street, Marriott maintains that it was actually a relatively luxurious place to lodge, and free at that…

Somebody sent me a picture of me stopping the other drivers and saying: ‘It’s all over, it’s all over’

Cevert's tragedy hits home

When Lotus offered him a Formula 1 drive for 1972, Scheckter told McLaren – with whom he had signed a three-year contract that paid £3,000 – and they buckled, giving the South African his F1 debut in a third car at Watkins Glen. He says he enjoyed his drive to P9, mostly because “nobody knew who I was”.

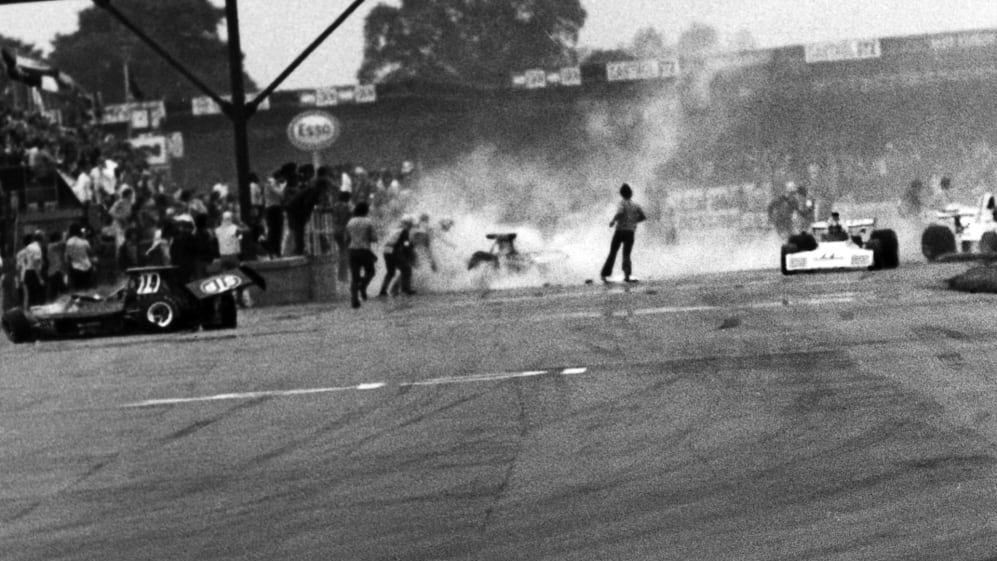

An argument with reigning champ Emerson Fittipaldi in France threatened to put an end to that, and the 1973 British Grand Prix did away with the last of any anonymity Scheckter enjoyed. In his fourth start, running fourth in the McLaren M23, Scheckter spun at Woodcote, hit the pit wall, then ended up in the middle of the track, collecting eight other cars in a colossal crash. Andrea de Adamich’s broken leg was the only major injury amidst the chaos.

McLaren sidelined Scheckter, who then raced Stateside in sports cars, and he returned for the last two races of 1973. With the knowledge that McLaren couldn’t keep him for the final year due to sponsorship issues, and that another seat would be opening up at Tyrrell with Jackie Stewart soon to retire, Scheckter had lined up a drive alongside Francois Cevert. But first, he had to clear the air with the driver lined up to be his team mate.

“I had a crash with Francois in Canada, so the next race was Watkins Glen [in ‘73]. I was going to be his team mate and I went to him at Watkins Glen and said, 'Listen, we’re going to run together, be friends, everything like this,' and it was all okay.”

Scheckter recalls the horrifying accident that unfolded before his eyes at Watkins Glen in 1973.

“During practice at Watkins Glen, I came out and he [Cevert] went past me, went in the barriers and the nose of the car was in the middle of the circuit, and I jumped out.

READ MORE: The lost champion? Jackie Stewart on ill-fated protégé Francois Cevert

“I remember trying to get his safety belts off. I remember turning around, I don’t remember what I saw. Somebody sent me a picture of me stopping the other drivers and saying: ‘It’s all over, it’s all over.’

“A big shock to me; it’s the first time I’d seen anybody die, and I remember thinking: well, everybody’s carrying on more or less the same. Somebody’s died, you know?

“But, did it change my driving style or anything like that? It probably came home to me that I could get killed. But I don’t think it changed anything from a driving point of view.”

Taking on Villeneuve and winning the title

Ken Tyrrell would hone the skills of his rough diamond and Scheckter won two races in ’74, finally picked up his home win the following year, and another in Sweden – at the wheel of the six-wheel P34 – in 1976. But he was tempted more by the promises of Wolf and their gold WR1.

The move paid off, Scheckter winning three races in 1977 to finish second in the championship – but the following year yielded no victories at all.

“The Wolf ‘78 was not good at all. It was supposed to be a wing car, but it really didn’t work. I think I did one or two good results but not a lot. The year before, I should’ve won the championship. That is the year that I could have, but I never thought, ‘I want to win the championship.’

“We had 20 people; Ferrari had 200. All I wanted to do is say, ‘Can I beat these guys, can I compete?!’ I remember James Hunt saying, 'Don’t worry about him, he’s won the first race, he’s rubbish, he’s out of the way,' because he thought that was it for me.”

Enzo Ferrari was, however, courting Scheckter, who avoided signing a mid-season deal in 1978 before jumping ship to the Scuderia in 1979 to partner Carlos Reutemann. As Reutemann moved to Lotus, Gilles Villeneuve would be Scheckter’s team mate in the 312T3 – the T4 to debut later on in South Africa.

“He had raced in one or two races or something, but I wasn’t worried about him,” he says of Villeneuve. “I don’t worry; first of all, if they’re not in the front or around me I don’t know who they were. I worry about myself, not other people, because I win or lose races by myself.

“But he won the first two races of 1979 – then I knew him!”

Scheckter hit back with P2 at home (after a slow pit stop cost him a shot at the win) and then took wins in Belgium and Monaco to top the standings. He would seal his championship at Monza, Scheckter leading Villeneuve in a famous Ferrari 1-2.

“I tell you what, the highlight is Monza 40 years later,” he says, “when I did that demonstration in the T4. That was probably the nicest of all, because it was only relief at Monza when I won the championship: f****** hell, I’ve been trying for seven years!

“My first year with Tyrrell, I could’ve won the championship – I left Monza equal on points – but I knew I could do it, it took me till '79, and when I won it in the last race, it was just relief, nothing else.”

Jody Scheckter drives 1979 title-winning Ferrari at Monza

As for Villeneuve, who died at the wheel in 1982, Scheckter describes how he had the measure of the Canadian – but adds that his team mate held up his end of the bargain in the 1979 title decider.

“Gilles’ weakness, he wanted to be a daredevil, that was his weakness. And that’s what gave me confidence. We went testing two weeks before Monza [in ‘79] at Ferrari, because we could go there for two days, and he was trying qualifying tyres and this and that – it was Gilles in the headlines. And I was just altering the car, altering the car, and I was quicker than him in qualifying and quicker in the race.

“As soon as [Jacques] Lafitte dropped out, I just led because we had a regulation within Ferrari: if you’re first and second, you don’t fight. If you’re sixth and seventh you don’t fight unless somebody else is going to overtake you. We stuck to that. Gilles was very honest, an honourable guy, and I was – we had a great relationship. I never, ever argued with him. I can’t remember having one single argument.”

READ MORE: 5 reasons F1 fans are still in awe of the legendary Gilles Villeneuve

Do the hustle

Championships sealed for Ferrari in style, Scheckter decided in the middle of the 1980 season that he would retire at the end of the campaign, which saw a baffling lack of performance from the Prancing Horse as they finished 10th in the standings. The South African began to consider his own mortality.

“One to two drivers were killed every year, out of 25,” he says. “The magic had gone out of it for me. It didn’t mean much to win the championship twice… are you prepared to die for it, Formula 1?

“You’ve heard of Gilles in Dijon [racing against Rene Arnoux in 1979], everybody thought it was the most wonderful thing and I said to Gilles: ‘You’re going to kill yourself doing that! You think it’s all smart and everybody thinks you're a hero. You touch wheels like that, and you don’t get out of it!’”

Retirement saw Scheckter try his hand at broadcasting in North America, but in the early 1980s he’d begin shooting for far more than that…

PODCAST: 1980 world champion Alan Jones on racing and winning for Williams

“So, I’m living in Monaco, I went out for dinner and went to a friend’s house, saw a magazine and in there was a guy with a live gun shooting at a paper screen and I thought: ‘Whoa, what a great idea.’ And my friend knew the company. I said, I want to export them to South Africa – I didn’t. I didn’t really have contacts in South Africa.

“A friend of mine had businesses in America and did some research and said that their law enforcement needs a simulator. He found a technician that said they were working with a prototype laser in a gun [instead of paper and holes] and I went over there, went to the FBI, said I’ve got this concept, and the guy said: ‘That’s nice.’

“I said: ‘I’m sure he’s being polite’ and I did a deal with the guy to give me a prototype and that’s how it all started. Went into the office with nothing, just started it, and then got to know consultants at Lockheed Experimental Department.”

In Atlanta in the mid-1980s, Scheckter formed FATS inc. a training company for military and law enforcement in the USA. Much like his Renault saloon days, he had to think on his feet.

“The first time I contacted the military, we didn’t even have a proper office. So, we filled in our diary [with scribbles] to make ourselves look busy, and outside I was putting our logo on a screen. This guy came up in plain clothes and I said, “No, the army’s supposed to be coming,” and he said: ‘I am the army.’

“Oh, but it worked out very, very well. I think after three years, I didn’t put any money in. The last three years were $29, $60 and $100 million dollars in sales. Three years after we formed it, went public, and then we sold it. That’s how I afforded this bloody place!”

.jpg.transform/9col/image.jpg)

This, er, place is Laverstoke Park Farm, which started in 1996. It’s spread across 2,500 acres in Hampshire, UK and produces artisan cheese, meats, ice cream, sparkling wine and more, educating children from schools about the process and winning awards along the way. It’s been a rewarding venture, but Scheckter reveals that it required a serious and perhaps unexpected commitment from him.

“I thought I was always a foodie, was always doing a lot of exercise, was by far the fittest driver at that time. I thought, ‘What’s the best lamb, what’s the best chicken?’ Again, hustling, like I did in America, and probably like I did when I prepared my own Renault car.

“You’ve got to find out who knows the best, talk to them, and that’s what I did. Then I realised if I kill a cow, I’ll have beef for eight weeks, so I bought the farm next door, started the business. Thought I was really smart because of what I did in America and built five factories and started eight sort of companies all to produce the best tasting, healthiest food, without a compromise.

“Now you’ve got to start making it affordable, and if I learned anything you can’t make money with food unless it’s volume. I also think my marketing and sales side was weak, because Formula 1 teaches you how to develop things quickly. I could develop products very quickly, but to market them probably was my weakness,” he says.

Now 73, Scheckter says he put an immense – perhaps excessive – amount of time and effort into his farm, while juggling his personal life along the way.

“I do want to slow down,” he says.

“I should’ve slowed down 10 years ago, but the company was failing at that time, and I didn’t want to leave a company failing. So, I went from 60 to 70 [years old] to get it back on its feet and get it working properly.

“If that’s a regret, it’s a regret. That’s what I had to do at that time.”